The Settlement Exhibition

The Settlement Exhibition

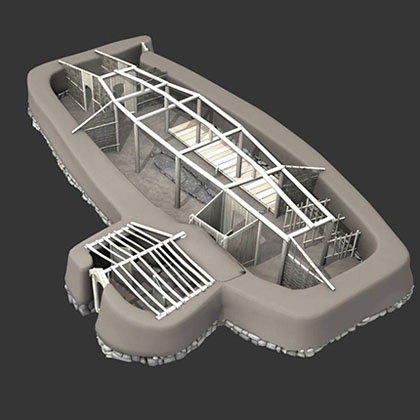

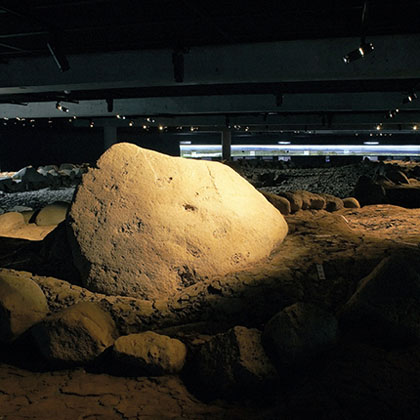

The Settlement Exhibition - In 2001 archaeological remains were excavated in Aðalstræti, which turned out to be the oldest relics of human habitation in Reykjavík. A wall fragment was found dating before 871 AD. During the excavation, a hall or a longhouse was found as well, from the tenth century. The hall and the wall fragment are now preserved at their original location as the focal point of an exhibition about life in Viking Age Reykjavík called The Settlement Exhibition Reykjavík 871±2

The Settlement Exhibition Reykjavík 871±2 is located in Reykjavík centre, Aðalstræti 16. See map.

Opening hours:

OPEN DAILY 09:00 - 18:00

Guided tour in June - August at 11:00 on weekdays.

Guided tours in foreign languages for groups (10+) are available by appointment.

Admission

ADULTS

1,700 ISK

CHILDREN (0-17)

Free admission

SENIORS 67+ & DISABLED

Free admission

STUDENTS WITH STUDENT CARD

1,100 ISK

ICOM HOLDERS

Free admission

The construction of Viking Age buildings is explained using multimedia technology. Computer technology is used to give an impression of what life was like in the hall.

The exhibition aims to provide insights into the environment of the Reykjavík farm at the time of the first settlers. Exhibits include artefacts from archaeological excavations in central Reykjavík.

Settlement Sagas

Written in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the settlement sagas look back to life in Iceland from the ninth century through to the period of Iceland’s Christianisation (in 1000 AD). They tell of settlers from Norway and the British Isles and the regions where they settled, detailing their family origins and noteworthy descendants and sometimes giving their reasons for leaving their homelands. These sagas record memories and tales from all quarters of the country: place names given at the time of settlers’ first encounters with wild nature, voyages to other shores, trails traversing the island and Icelanders’ endeavours to enact order through a law code and an annual general assembly, where the population attempted to resolve disputes involving boundaries, land use, love, power and murder. At the same time, the religion of this new society was making the transition to Christianity.

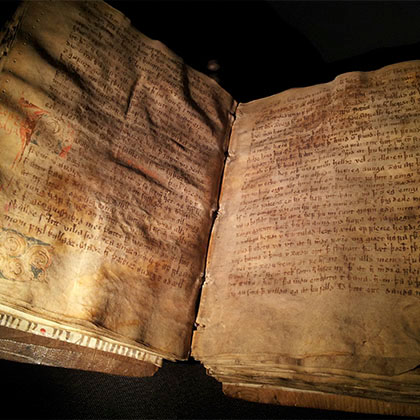

Some sagas are composed in the style of history, such as Íslendingabók (Book of Icelanders), compiled by Ari the Learned in the 1120s, and Landnámabók (Book of Settlements), preserved in two manuscript versions from ca. 1300. Others belong to a group of narratives known as the Icelandic family sagas. Although regional in their settings, their plots are intricately interwoven. The annual assembly or Alþingi is often a meeting point for characters and storylines alike.

The world of the sagas is unique and internally consistent: a portrait of a new society in a previously uninhabited land. These narratives have no parallel in world literature. The extent to which they depict real people and events is uncertain, but the external reality of the sagas – their chronologies, conceptions of origins and religion, recollections of the natural environment and accounts of volcanic eruptions – tallies well with what can be gathered from other sources. A degree of continuity can thus be stated to exist in oral traditions from the time of Iceland’s settlement to the period of writing, even if this continuity need not be a measure of the sagas’ veracity.